Butter Side Up Theatre Company’s The King In Yellow – 8 March 2024, Theatre Deli Sheffield

Review by Peter Taranaski.

The Sheffield-based group return to the Theatre Deli and aim for the deep, deep stars with their latest play, “The King In Yellow”.

“The King in Yellow” is a play adapted from a collection of short stories by Robert W. Chambers back written back in 1895. They are an early example of cosmic horror, a genre that fits somewhat snuggly between Poe’s literature and the influential Cthulhu mythos (Lovecraft). Cosmic horror is a branch of weird horror where supernatural and extra-terrestrial elements combine in phenomena which is, ultimately, beyond our science, understanding and morality. When these forces / creatures / gods interact with humans, or humans seek to understand their experiences; it generally ends up in madness. Despite it’s unknowability there is a certain compulsive lure to this knowledge, and grasping towards it is often the same as grasping towards madness. The joy of watching cosmic horror is it’s attempts to translate this abstract threat into reality and how the encroaching madness humbles us as a race, tempering our hubris about our scientific accomplishments.

The original play has mostly been lost with only fragments still surviving, though the book references some of the content, so it is certainly a joy to see the play today in an adapted form. It is split into three parts, “Act One: The Repairer of Reputations”, “Act Two: In the Court of the Dragon”, and “Act Three: The Yellow Sign” with a path between all three being a crooked yellow brick road, recounting madness in it’s different guises. We went in not reading the original book, but having read a lot of the proceeding Lovecraft novels that occasionally references this.

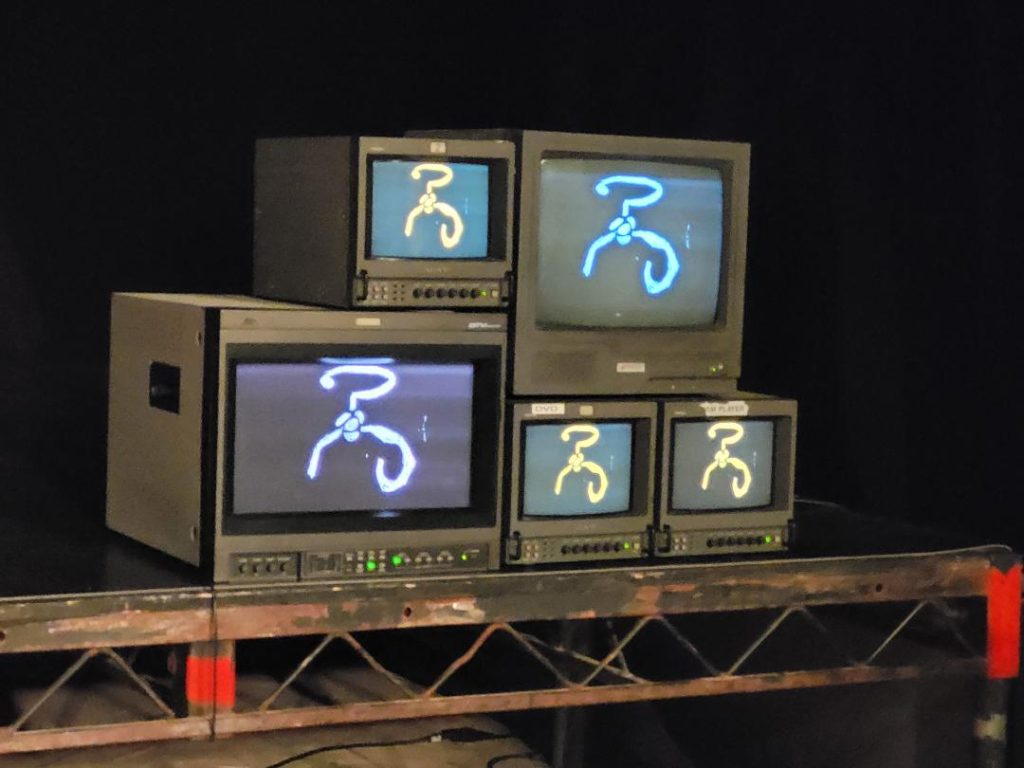

On entry to the play it is apparent that effort has been put into the ambience and feel of the production. There is music as we wait with a lot of darker sounding stuff from the 80’s, but not exclusively so. The audience is full, there is lot of excited chatter and appreciation of the “Eldritch-themed light” by one party. The kind of sickening green / yellow light is indeed around, on the stage are a series of old televisions with the “Yellow Sign” sitting in the static. As the beginning drew near these symbols multiplied, and we saw brief flashes of light, it was more than just a good (yellow) sign of the effects to come.

It all starts with Hildred (Andrew Wilkinson) returning to live with his brother Louis (Connor Varley) following a “concussion” and a spell at a “private institution”. He is still in contact with his consultant psychiatrist, Dr Archer (Jonathan Hurd) and Louis has a blossoming relationship with Connor (Daniel O’Key). Hildred finds a book in his bag that has appeared out of thin air, “The King in Yellow”, a play above all plays with it’s transcendental contents and starless metaphors the grab hold of Hildred. This book has already worked it’s spell on Wilde (a You-Tube content creator) and will influence Jack (an artist / photographer leaning sibling of Connor), and Tessie (muse and partner of Jack) in various ways throughout the acts. Each member with a loving, supportive element in their life is consumed by this otherworldly material and visions of Carcosa, a strange place where a message has come, a message of revolution. Kudos must be given to the writers in this regard (Max Marriott, Scott W. Gist) as the story has been adapted for modern times and tackles current issues, most notably in the shape of Wilde (Rob Eagle), a kind of Andrew Tate of otherworldly knowledge. Eagle plays a hacker who has deluded himself of a higher purpose “like Robin Hood” except his dreams have pointed him towards starting a cult by syphoning money off the big and powerful. Eagle’s grating on-screen persona gets big laughs when he first appears with his selfie stick and grinning ego. As the play progresses we see his characterisation delightfully dripping with desperation and greed; and in his very best moments, hesitation and awe about the hints of a prophecy being fulfilled from his sleepless dreams. The play’s look at social media, inclusive characterisations, commentary on radicalism, and ultimate focus on trauma demonstrate writing that has transplanted an old text very convincingly into the body of modern society. In showing us the growing insanity with this handful of characters, the play hints at a society engulfed in a growing mania by describing the book itself as an invasion of the play into mainstream media and it’s effect on it’s readers. This has more than faint echoes of the aforementioned Tate and current concerns about harmful ideologies such as the Manosphere. The culmination of these themes is a dialogue about the effects of trauma and the people it affects around it. At first, we thought that Dr Archer’s focus on trauma being the cause of three characters’ mental state at the end was too contemporary an angle that lacked nuance. But in reality, we fell into a trap, just like the main characters. If something like this happened now in real life, it’s unknowability would be no different to when the play was originally written. Mental health professionals would be as unbelieving in 2024 as in 1895, and would try and point to whatever is the hot topic of the day to understand a mystery too great for the human psyche to pierce with any real level of understanding. This is exactly the point of cosmic horror. Hurd portrays this aspect well in his doomed quest for knowledge. If we have a minor niggle it is probably the use of the word “institution” and how the concepts around mental health detention are explained. If the play is set in the last 15 or so years (due to YouTube and social media being present), this way of understanding treatment and detention in an “institution” has been defunct since the 80’s (even in the USA). It feels a little out of place among the contemporary themes woven in, but it’s presence here is probably just grist from where modern and original writing has intersected and the character of the old work is sought to be retained. As we say, it is a minor niggle which many people not working in the area would not notice let alone mind.

There is a lot to like in this play from the acting to sound and visual design and also choices over the use of space. There are memorable scenes such as Hildred standing on a sofa with a tin foil crown on his head and his representation as a delusional demagogue. There is Varley’s “Louis” and the look on his strained and compassionate face for his brother’s attempted rehabilitation. Daniel O’Key’s heavy lifting of portraying a boyfriend (Connor) who undergoes his own transformative journey from caring, funny and “the soul of the party” to a misanthropic, fearful and troubled trauma victim is truly excellent and nuanced. We also liked Jack’s (Ash Wilkinson) quiet frustration, and The King’s truly blood curdling appearances and delivery (Michael Winrow) and several of the ensemble cast’s truly demented stares that could have only come from the darker reaches of Jack Nicholson’s psyche (Anthony Garbett, Harry-Lynch Bowers, John Ashmore). Faduma Hassan’s Tessie is a masterclass in naturalistic performance, projection and presence which we enjoyed very much.

An example of a truly excellent scene is when Connor goes to church and experiences nightmares. Connor is sat down from the stage looking to the audience, the congregation is looking up at the pastor. As the scene develops the chairs are turned, the actors faces become hidden under masks and they slowly all turn their yellow gaze on to Connor. Creepy and nervy in execution it is flawless. Towards the end of the first act there is a physical altercation between characters which is also well choreographed and believable in it’s biting realism. These are counterbalanced with the scenes of domesticity and light relief (such as on the beach in Spain or the pub quiz) where there is a little levity and flashes of possible future job for all the characters. All the movements of the set are accompanied by the aforementioned televisions flashing up unsettling, otherwordly visages such as twin suns and faceless humanoid threats, the voice as deep as volcanic rock chants “The Yellow Sign” and some of the characters call out the verses of the dooming play. The stage is a clausophobic kaleidoscope brought to life by the lighting, sound (Jamie Cooke and Coltan Holland) and visual effects (Ghoul A/V, Rob Lee). Notable costumes (Jane Wade) were the black masks with their gold gilding, the visage of the Yellow King himself, and also the makeup that is worn by the image of insanity that Jack sees in the viewfinder of their camera.

This is a great play through and through. The means of making cosmic horror enticing requires good acting and a creative mind able to translate the abstract and idiosyncratic into something the audience can understand. Seeing people going mad for hours on a stage, in itself, can be incredibly cringeworthy without a deft hand at the wheel. Here the direction (Max Marriott), set pieces and acting, all come together in a highly professional and technical accomplishment that evokes dread and fear in every space and in ways that others could only (uneasily) dream of. Bringing this work up-to-date is a difficult task to accomplish, but one that is completed here with a sense of Eldritch style and flair.